Video Games Need More Signed Urinals

When I first learned about Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, my reaction was blind rage. In my defense, this was in my high school AP Art History class, and in high school my reactions to most things were some variety of rage. I saw Fountain as a transgression, a lazy hack's attempt to generate controversy by shoehorning a stretch of an idea into a conversation about art.

For the uninitiated, I don't want to inundate you with technical jargon, but Fountain is what people in the art world refer to as "a goddamn urinal". Here it is:

Duchamp purchased a urinal from a local hardware store, flipped it over, signed it, and submitted it for exhibition by the Society of Independent Artists, an organization of art exhibitors which Duchamp himself helped to found, and whose board he sat on. Fountain was submitted as a sort of test of his fellow board members' dedication to the philosophy of democratic exhibition and to free expression. The board voted to remove Fountain from exhibition, and Duchamp resigned his board position in protest.

In 2011, I sided thoroughly with the rest of the board of the Society. This is not art, I thought, art is paintings of Dutch nobility, and the Pyramids, and marble Olympians with small penises! You can't just sign any old piss receptacle and call it art, where is the technique, the craftsmanship, the dedication?

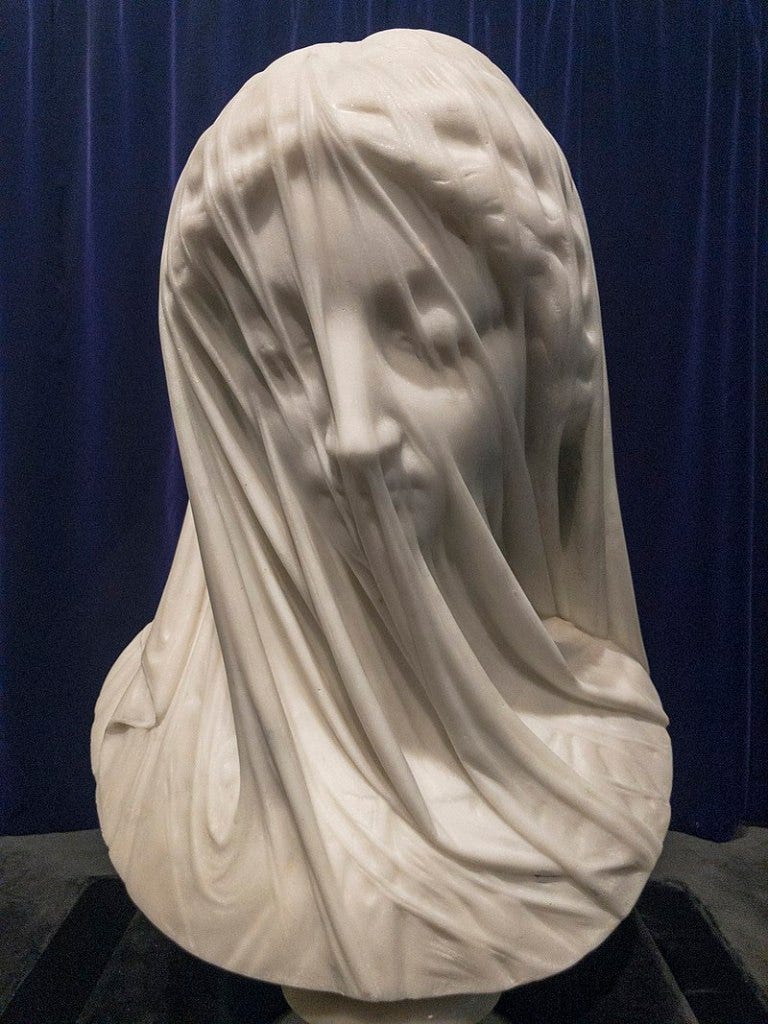

As time went on though, my opinions about art in general and Fountain in particular started to move. At the time, I might have pointed to the great marble sculpture of the Greeks, Romans, and eventually Renaissance and post-Renaissance Italian masters as the apex of art. Truly, to carve solid marble into a form and even seemingly a texture resembling flesh was a sign of a true mastery of the medium. Look at The Veiled Virgin by Giovanni Strazza; not only did Strazza create a perfect simulacra of a woman's head out of marble, he then veiled her. Can you imagine the technical skill you need to turn white marble into a translucent veil?

Here's the thing about The Veiled Virgin, though, is that it doesn't actually make me feel anything. No thoughts are implanted in my mind by The Veiled Virgin. It's almost as though it is so close to reality that my brain just doesn't have the square footage in the possibility space to imagine anything. My only thoughts are "Wow, yeah, that looks like a woman wearing a veil. I bet that was really hard to do. I couldn't do that". I don't mean to insult the talent of Strazza or the many other talented sculptors of this style both working today and in history, but this is the same response I would have to someone grabbing a piece of chalk and drawing a perfect circle freehand on a chalkboard. I don't ponder it, it's not sublime, I just go "man, dang, that's a good circle".

Meanwhile, even when my anger towards Fountain faded, I still found myself thinking about it constantly. This seems as though it was Duchamp's intent, to encourage the audience of an artwork to spend less time considering the terms of its creation, and more time considering the ideas contained within. Fountain feels, like so many pieces of modern art, laser focused to trigger the gestalt, a very human part of the brain that takes incomplete images and attempts to use what it knows to complete them. To one used to thinking of artwork as the craft of the old masters, a urinal with a name on it is an incomplete thought, and the brain is forced to truly think about it to complete the thought. Instead of going "man, dang, that's a good circle", you begin with that most trite but useful of questions for modern art: "what does this mean?".

That thought process, that slow mulling over of a piece in my head, trying to construct a framework of ideas that the work makes sense in, is infinitely more interesting to me than just appreciating the fine chiselwork of a sculptor or the delicate brushstrokes of a painter, it is a sort of puzzle box that forces me to not only consider the work itself, but the world around the work, in hopes of finding a clue within the environment that will make Fountain click open like the Lament Configuration, that will make the thought complete.

As an aside, Fountain's most consistently funny unanswered question for me is that posed by its origin: Fountain is a urinal, and urinals are very much built with a meaning in life already assigned to them. In a section obliquely labeled "Interventions", Wikipedia goes on to describe the multiple times one or more people have attempted to pee into Fountain. Multiple people have succeeded.

The philosophy laid out by Duchamp would later be expanded upon by a lesser-known artistic movement called Fluxus, one I am extremely fond of. Fluxus artists returned to the artistic process held so sacred by traditional art critics, and found that even the process itself could be a vehicle for ideas and meaning, even to the point where the actual end product is rendered almost a leftover of the process. More renowned artists of the movement include Nam June Paik, John Cage, and Yoko Ono, but I want to talk about one Dick Higgins.

Dick Higgins is considered a co-founder of the Fluxus movement and worked in a variety of mediums, but I'm the most interested in his music, most notably a set of pieces called Danger Music, which went on to give its title to an entire genre of experimental music. As its title implies, the defining characteristic of danger music is that the performance of danger music must put the musician, the audience, or both into physical danger. One piece of danger music requires a live grenade to be thrown into the audience, another demands the performer "scoop out one of your eyes 5 years from now and do the same with the other eye 5 years later". Danger music project Hanatarash once drove a bulldozer into a venue. The performance of danger music is the point; listening to a recording of a danger music performance loses all meaning, unless one really enjoys the sound of panes of glass shattering in a crowded concert venue.

Danger music's mere existence raises so many interesting questions about music as an art form that I could frankly divert this entire post to just asking them. Do musicians have a responsibility to produce music that is safe? Is a piece of music still beautiful, still valid, still a complete work of art, if it is never performed, like that live grenade which has yet (to my knowledge) to be thrown into a crowd? Some genres of music, particularly metal and some more boisterous hip-hop, are meant to be played excruciatingly loud, to the point where they could cause very real hearing damage. Are these songs dangerous?

I bring up Fountain, Danger Music, and Fluxus because the kind of art I find the most interesting is that which is very openly disinterested in reveling in craftsmanship, instead focusing on using available media, techniques, and tricks to force the audience to think, to produce a new idea or worldview it wouldn't have without it, whether that process requires a master sculptor's years of experience or a Sharpie and a trip to Home Depot. Here, finally, after over 1000 words, I'll talk about video games.

Perhaps as a side-effect of the tools used to create video games still being so young, the discussion of video games as craft still heavily focuses on the craftsmanship around them. Popular discussion of video games, even by people who would openly consider them to be "art", is dominated by metrics of technical achievement: the framerate at which they run, the graphical fidelity of the game's world, the sheer size of the game's space for play, how many ping pong balls you can tape to a horse in a mocap studio so you can accurately simulate how its testicles will shrink in the winter.

To me, no game signifies this philosophy quite like The Last of Us. A 2013 game by Naughty Dog drawing heavily from The Road, No Country for Old Men, Resident Evil 4, and Ico, The Last of Us was a massive financial and critical success, and was in many cases a masterpiece of the craft of video game development. The game looks absolutely gorgeous, even more so with its HD remaster for current-gen consoles. The music is haunting and beautiful, the animations vivid and smooth, with every physical strike against an opponent being unflinchingly realistic. The writing is also excellent, helping to bring the lead characters, the grizzled and world-weary Joel and the youthful and hopeful Ellie, to life. The incredible motion capture put into these characters also certainly help to bring these two characters to reality.

While I have not played The Last of Us Part II, it seems to very much be carrying on that legacy, with game design Twitter going bananas over the game's incredible rope modeling, and the fabric physics exhibited when a character takes off their shirt (these sound remarkably pedestrian, but fabric is about as hard to render in pixels as it is in marble).

The thing is that The Last of Us makes me feel nothing, just like The Veiled Virgin. Its dedication to strong writing and to beautiful visuals and to grisly, realistic violence don't lead me to think about it, don't force me to scour the world for a framework in which to understand it, what the game means is laid bare. All that's left for me to think whenever Joel brains a clicker with a fire axe is "man, dang, that's a good circle".

Den vänstra handens stig is a video game I saw at PAX South in 2016. A one-man project with relatively simple pixel art, Den vänstra handens stig lacks what one would traditionally call "controls", despite being of a kind with traditional platformers like Super Mario Bros. Instead, the game character is controlled by an AI, one which repeatedly tries and fails to clear the game's levels, with each death causing the AI to learn a bit more about the best strategy to take on the game.

The singular control of Den vänstra handens stig was a single button on the show floor, hand made in a wooden case. The button, which is actually designed to have a needle sticking out of it which had to be removed to comply with PAX rules, actually does a lot: it kills the player character instantly, completely wipes everything learned by the AI, and restarts the entire game from scratch.

When I saw this game at PAX, I was entranced by it, and the struggles of this AI doofus as he tried and failed and tried and failed and tried and succeeded at traversing his hopeless little world were enthralling. At a certain point, a group of spectators, including myself, formed something of a phalanx around the button, aiming to protect it from people passing by on the show floor, who might be compelled by either malice or the haunting allure of a big button to reset the entire game.

Den vänstra handens stig is a game I think about constantly, even though it seems like development has stalled since 2016. To what degree is watching a video game being played playing the game? When we lose at a video game, when our progress is reset, or worse, when we simply cease to play a game, and all lessons on how to play it seep slowly from our memory, what does that incomplete play experience mean? Why is the proposition of completely obliterating all progress in the game, even when it might literally hurt me, so innately tempting?

When the game was initially put on Steam Greenlight, Valve's now-retired stab at allowing the community to vote on what games would be put on PC game marketplace Steam, a lot of the comments were extremely dismissive of Den vänstra handens stig. Here are some direct quotes:

"it seems that all you do is jump over holes and climb up ledges"

"This is terrible. Why would you submit this?"

"Oh this is deeply unpleasent. This is NOT okay!"

"Tired of these kind of games, so no. Also way to create one of the worst names ever for a videogame. Just damn."

When I look through these comments (although I must admit a lot of these are positive, and the game eventually did pass Greenlight's approval process), I kind of think of them like the board members of the Society of Independent Artists, dismissing Fountain as just a urinal, and as some vulgar piece of trash not worthy of exhibition. I think of teenage me in 2011, declaring that this is not a video game, video games have guns and murder and numbers that you make bigger so you can kill people better and big maps full of icons for all of the street races you can do. Surely, much as I thought that an artist had to at least make his piece instead of just buying it, I might have thought that surely a video game at least needs to have controls.

While Den vänstra handens stig never formally came out (to my knowledge), other games of its kind have. Every Sale I Drink A Glass Of Water is pretty much exactly what it sounds like: an ever expanding video of the creator drinking a glass of water every time someone buys the game. Like Den vänstra handens stig, Every Sale does technically have a control, it's just that the control input is the act of purchasing the game.

Moirai, a ten-minute adventure game now unplayable, placed the player in a deeply uncomfortable position. Sent into a cave to investigate suspicious moans heard from within, the player encounters a strange, knife-wielding man who looks extremely suspicious, and is sometimes drenched in a blood spatter. After some questioning, the player can let this shifty man pass, or kill them, before progressing deeper into the cave to find a woman wracked in pain, suffering from a botched suicide attempt. She hands you her knife and asks you to finish her off. If you don't oblige, she splashes her blood at you in a fit of rage. Upon resolving the encounter with a woman, on your way back up, you are confronted by a farmer, who subjects you to the same line of questioning you posed the knife-wielding stranger when you entered the cave, and then you realize that you are the knife-wielding stranger drenched in blood. Every time a player enters the cave, they are greeted by the saved responses of a player exiting the cave, and from those responses and without the knowledge that they are simultaneously confronting another player and essentially their own future self, the player will decide whether or not this figure will die.

These games are not masterpieces of craftsmanship. These are either one man projects or small team projects, mostly built by non-professional developers. They don't use the latest technology, they don't have exquisite graphics or perfectly crafted dialogue or delicately-tuned combat, but they are the perfect vessels for ideas, ideas which plant themselves in my head and make me spin them around while I lie in bed, looking for the angle at which I can fumble together an answer. I enjoy this process greatly, and every time one of these big budget AAA video games full of realistically rendered violence and horse testicles barges into store shelves, I find myself wishing that budget was instead cannibalized to fund a million Death Buttons or Glasses of Water or Recursive Farmer Murders.

I write this as something of a call to action, both to the reader and to myself. The vast budgets and photorealistic graphics and mocap studios might seem like an imposing barrier around the realm of game design, one which is as impossible to imagine achieving as creating translucent veils out of marble, but that is not what a good video game has to be. This model of what a video game is not only serves to dissuade people from playing with the medium, but also closes off the possibility space to a variety of ideas that cannot be expressed by the normal model.

Make something sloppy and simple and dumb, as long as you have an idea to bring to reality. Having that idea and expressing it is more important than anything, including the need for the thing you make to even be recognizable as a video game. Go grab your sharpie and sign a urinal. Then maybe pee in it.